I spoke with an engineering project manager recently where he shared a problem his organization faces. He said, “We are good at managing our teams to accomplish our projects. But we are not good at coordinating the resource needs of all the projects we have going at once, as well as the potential ones we have in our sales pipeline, and we are seeing operational issues from this.”

He described the frustrating fluctuations between frantic busy times where there is pressure to add more staff, and once the frantic period was over not being prepared to make good use of slow times from periods of underutilization.

Being prepared for slow times is part of the story, but from a bigger picture what we really wanted was what Lean practitioners call “level-loading”. We wanted to schedule our project work to smooth the demand for our resources. And when fluctuations were inevitable, whether busy or slow, we wanted to see it coming ahead of time so we could make a better plan. We came up with an idea we want to share.

Level Loading

The idea of level-loading comes from the field of Lean Manufacturing but has been expanded into all kinds of industries. Lean Manufacturers prefer to supply a mostly steady production run across the various products they make, rather than producing large inventories of one product then switching to another. They find that they make fewer mistakes this way, reduce inventory levels, and keep their supply chain running more smoothly.

In project management it would be smoothing out the demand for project work so that you are not always trying to add more resources to accommodate a spike in activity, only to lay them off when your project is done. In some fields (construction, for example) that’s inevitable to a degree. But in many fields onboarding new team members is difficult and time consuming (read CV’s, conduct interviews, initial training, etc.), as well as risky (what if after all that work, there are problems we didn’t see coming?). It’s often better to keep steady work for the team members you already have, and only onboard new ones if there’s a long-term need.

How can we level-load our project teams if the demand for project work is always changing? Let’s look at the ways companies normally manage their resources now1 and some of the problems they face with answering this issue.

Resource Capacity Planning

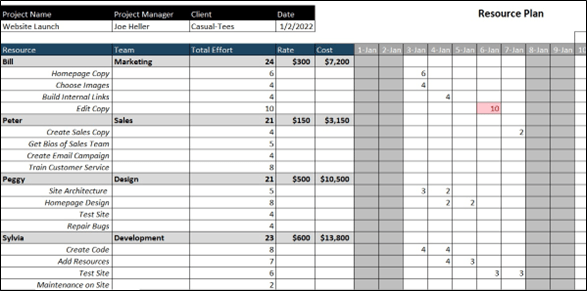

So you have a project team, working on a project. Approaching the question from the “Team” side, you might ask, “What will my team be working on during the next week/month/etc.?” Many companies use Resource Capacity Planners to answer this question. They can accommodate multiple projects, and often look something like this:

Two problems:

- In most cases, there is no natural link between capacity planning for team members’ assignments and the resource requirements of ongoing projects, much less the ability to plan potential projects. This means that it is difficult to evaluate scenarios such as, “If we win this contract, will I need to hire an additional person?”

- Visibility into resource optimization (i.e. avoiding overloading team members and taking advantage of lulls of underutilization) is sometimes limited to short time periods. For example: Are multiple projects projected to reach peak utilization at the same time? It can be hard to spot and act on larger patterns using a tool like this.

Project Resource Requirements

Approaching the question from the other side, the “Project Work” side, you might ask, “What work needs to be done?” And the natural follow up questions are, “When should the work be done?” and “Who will do this it?”. The result is a time-based representation of a team-member’s estimated workload, like the Capacity Planner we already talked about. However the benefit is that the estimate is closely tied to project work.

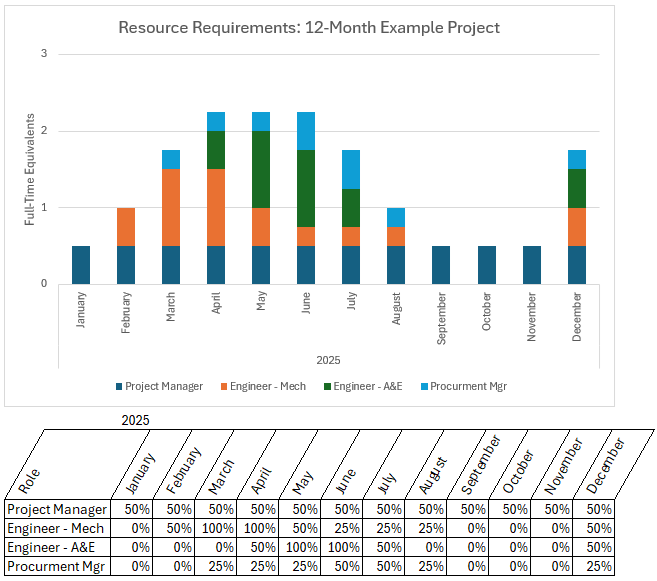

The Project Management Institute (PMI) in their Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK), which is sometimes represented in what PMI calls a Resource Histogram, or a resource utilization chart, something like this:

Some project managers don’t like to use this chart because it states the obvious: There are times where you will need more resources on a project and times when you will need less, and it’s helpful to know when those are. While the chart isn’t mandatory according to PMI standards, and many companies don’t use it at all, I introduce it so I can build on it.

Here’s the key idea: Can I use this tool to understand the resource requirements of more than one project? How can I evaluate scenarios to help me reduce overload or take advantage of underutilization?

Resource Requirements – Multiple Projects

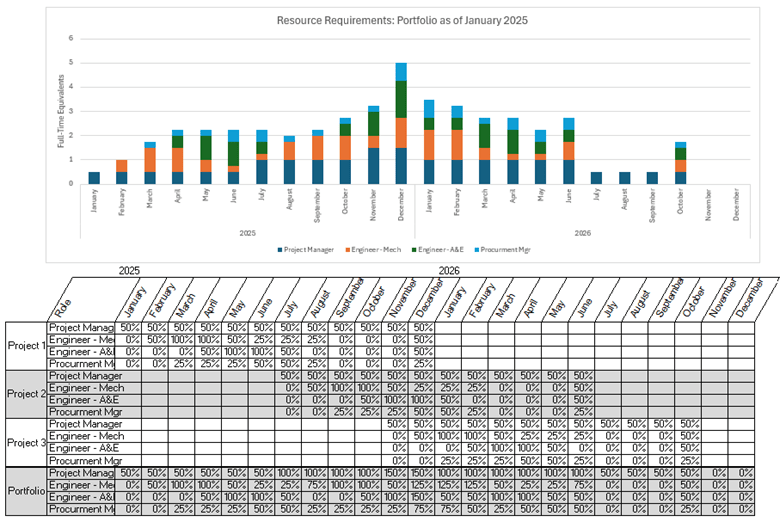

Let’s see what happens when I overlay more than one project onto the Histogram template? It will look something like this:

In this example we now have some meaningful insights:

- There is a spike in activity period predicted in December 2025. How are we going to deal with that? Perhaps we could get a temporary resource just for that month. Or perhaps there’s a way we can smooth out the spike so we can accommodate it with existing resources.

- There is a slow period predicted in July-September 2026. It’s still a long way in the future, so maybe we can win more projects by then. Or maybe we can use that time for an internal project we want to do.

- Narrowing in on specific skillsets shows that certain disciplines may be slow, even while the project team as a whole is busy. How can we make value-added use of these team members during slower times for their specialty?

Conclusion

By creatively applying the tools we already have (i.e. resource utilization charts and capacity planners) with frameworks we already know (e.g. level-loading), we can get more insight into problems our organizations face and how we can add more value from where we sit as project managers.

- An important exclusion: Some companies use MS Project or similar dedicated Project Management software for managing resource allocations, but I’m not going to talk about that. The first reason is that there are cost and IT barriers to entry with using these types of software, so only certain types of companies use them, with the others sticking to spreadsheet or cloud-based tools (Smartsheet, Trello, etc.). The second reason is that even for companies that use MS Project-type tools, there is a learning curve to using them effectively. Many project managers I’ve worked with, even in companies that use it, never get truly proficient with MS Project. ↩︎

Leave a comment