In Part 1 of this series we introduced the topic of risk, and why it deserves more attention in how we manage projects, and tools we can use to counter our own blind spots in identifying risks.

In this post we will discuss what to do with this list of identified risks. Which of them are the most important? Which should I spend my time dealing with? Or which are so minor that they do not deserve your attention?

Using the Risk Register

In the last post we introduced the Risk Register. Initially the risk register is just the place to record all the identified risks, without worrying about which of those were the most important.

In this stage, we will flesh out how to use a risk register to measure and respond to the risks in a project. Here’s PMI’s description of where we’re headed (emphasis mine):

A risk register is a repository in which outputs of risk management processes are recorded. Information in a risk register can include the person responsible for managing the risk, probability, impact, risk score, planned risk responses, and other information used to get a high-level understanding of individual risks. 1

Notice some key elements:

- Probability, impact, and risk scores

- Planned responses

- Person responsible (owner)

So now we’re looking at a document that looks like this:

Let’s dig into what these extra columns mean and how to use them.

Measuring Risk

To put a number to risk, include these two parts: (1) probability of occurrence, and (2) the impact to the project if it does occur:

Risk = Probability x Impact

It can be helpful to assign a scale or rubric to probability and to impact ratings to ensure you’re being consistent with your scoring. For example, an event with >10% probability of occurring would be scored what? Or an impact of $50k-75k on the project cost would be scored what? Or a schedule impact of 2-3 days? The details of your scale will depend on your project.

Assign a probability rating and an impact rating to each risk and multiply them to get a score for each risk. This will tell you which risks you should prioritize in planning your risk responses.

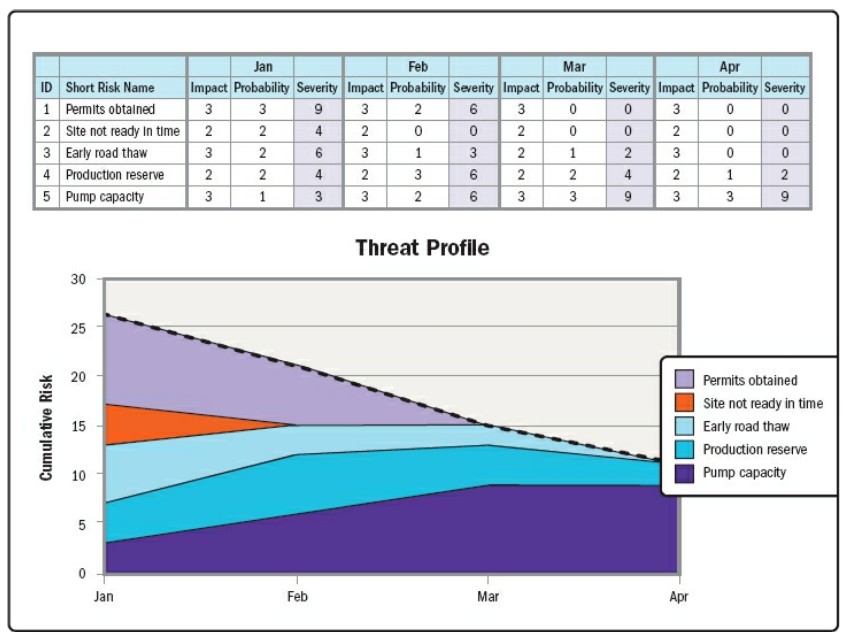

Note the sores for each risk can change over time. As an example, PMBOK offers this chart as a way to show how risk can decrease (or increase) over time as you implement your risk responses and circumstances develop. You will see that some risks disappear entirely, while others grow.

Why does this matter? Because it gives us areas to focus on. The goal of this exercise is to take action on the most impactful risks. Now that we know which are the most impactful, let’s look at what we could do about them.

Responses to Risk – What to Do About It?

There are five (5) general strategies for dealing with threats (negative risk), as summarized by PMBOK2:

- Accept. Threat acceptance acknowledges the existence of a threat, but no proactive action is planned. This could mean doing nothing at all, or it could mean doing nothing proactively but having a contingency plan if the event does occur. (Example: We know that cars can crash, but we still drive anyway)

- Avoid. Threat avoidance is when the project team acts to eliminate the threat or protect the project from its impact. (Example: If driving a motorcycle is too dangerous, drive a car instead)

- Mitigate. Action is taken to reduce the probability of occurrence and/or impact of a threat. Early mitigation action is often more effective than trying to repair the damage after the threat has occurred. The goal will be to reduce the risk down to a level where it could be accepted or transferred. (Example: We use traffic laws and safety standards for cars to reduce the probability and impact of car crashes)

- Transfer. Shifting ownership of a threat to a third party to manage the risk and to bear the impact if the threat occurs. (Example: We buy an insurance policy for certain types of risks)

- Escalate. Escalation is appropriate when the project team or the project sponsor agrees that a threat is outside the scope of the project or that the proposed response would exceed the project manager’s authority. (Example: Talk to your sponsor if the problem is above your authority to solve)

Risk Owners

The Risk Owner is the person who is ultimately responsible for ensuring that the specific risk is managed appropriately. This person should be involved in planning responses to the risk and ultimately deciding whether a risk falls within the organization’s risk threshold. Sometimes these are within the project team, and other times they were external to the team.

In my past industrial projects, we would always have risk owners from operations and maintenance teams, but it was also common to have risk owners from safety, quality, procurement, IT, and the list goes on depending on the details of your project.

Conclusion

This post continued our discussion about the Risk Register and what it should include in terms of scoring risks according to probability and impact, and how that should guide your risk responses. We briefly discussed Risk Owners and how they should be included in planning risk responses and evaluating risk against the organizational risk thresholds.

Next post will focus on the routines of Risk Review meetings, and how to use the results to communicate about risk with stakeholders.

A common sense note in closing – PMI says3 that a common problem is to spend lots of time analyzing risk and planning responses, only to not take any action on the risk responses. Please follow up on your risk responses to ensure you are taking the actions you agreed on. These should be reviewed during Risk Review meetings, a topic for next post.

Leave a comment