I’ve been writing a lot on risk lately and how we can manage it in our projects. It’s been a bit theoretical up to this point, so here’s a fictional and oversimplified case study. I’ve intentionally chosen a job I’ve never done before, as the point of the post is not to tell you how to do a specific project, but to introduce you to the process of managing risk for a project you’ve never done before. That said, if any of my readers are more experienced in real estate than I am, please feel free to write me to point out any serious errors I’ve made.

Fred has coffee with his friend who tells him about all the money he’s been making flipping houses. Fred has moderate construction knowledge, but has never flipped a house before. Fred decides to go ahead with the project and search for a house to flip, but he will want to pay special attention to the risks of the project because it’s his first time doing it.

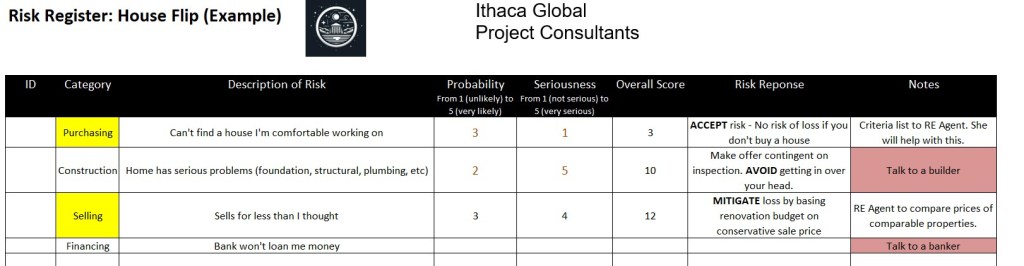

Fred starts recording all the risks he can think of in a risk register, grouping them by category (remember our Risk Breakdown Structures?):

- Purchasing

- Can’t find a house I’m comfortable working on

- Construction

- Home has serious problems

- Selling

- Sells for less than I thought

- Financing

- Bank won’t loan me money

Fred doesn’t know how to score the how risky these are, so he talks to a professional (expert advice). His friend connects him to the real estate agent he uses, and they set up a meeting.

The real estate agent walks Fred through the buying process and shows Fred tools that can help him narrow the search for the types of properties to buy and sell and for predicting sale prices based on comparable properties. The agent advises him to make a list of criteria he is looking for in a home, and they can work together to find a home that meets them. She also shares that inspections are a common part of home sales, so you can make your offer contingent on having an inspection done, so you can back out of an offer if something serious comes up in the inspection. Regarding pricing fears, she affirms that it’s a real risk but suggests that if you buy a house on the low end of the prices that houses are selling for, it will be easier to estimate the price of the renovated house based on the data from other more expensive houses in the area, and that could help with establishing your renovation budget. Regarding other concerns, the agent advises you to talk to a builder for the construction questions and to a banker for the finance questions.

Based on his conversation with the real estate agent, Fred starts scoring his risks in terms of probability and seriousness and planning risk responses ( Recall the main 5 risk responses: Accept, Avoid, Escalate, Mitigate, and Transfer.)

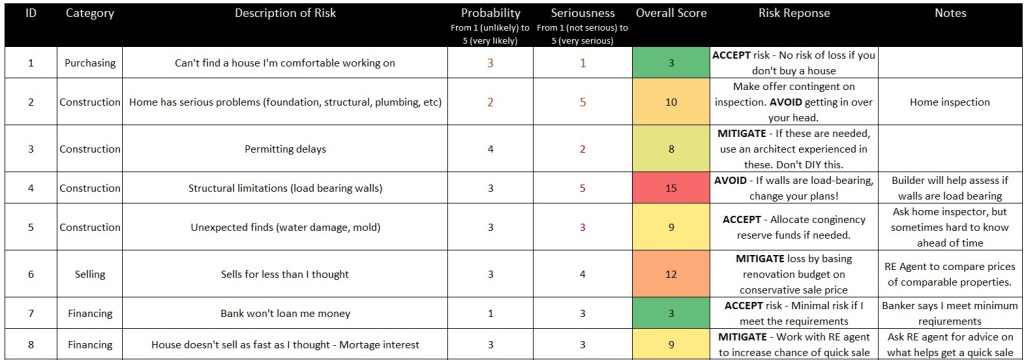

Fred has conversations with the banker and the builder. The banker assures him that he will be approved as long as he meets minimum requirements, which he does. However, given the plans to resell the house, the banker reminds him of interest rates of mortgages. If Fred doesn’t sell the house as fast as he hopes, he will continue to pay interest on the loan, which will affect the project budget. But the builder suggests some more risks he should plan for, especially when Fred tells him that part of his strategy is to make open floor plans to raise the final selling price.

The builder suggests that it’s hard to be specific without a specific property in mind, but in general he should plan for these risks:

- Permitting delays

- Structural limitations (load bearing walls)

- Unexpected finds (water damage, mold)

Fred adds the risks to the register and starts working with his RE agent to find a house. Here’s the risk status when he begins execution phase:

At this point, Fred learns something about himself. Because this is his first project of this type, Fred is Risk Averse. Even though he has taken on this project, Fred’s risk appetite is low. In particular, Fred is concerned about Risk ID # 4: Structural limitations (load bearing walls). His builder has assured him there are ways to deal with removing load bearing walls, but they all involve engaging a structural engineer and the work arounds may seriously affect his budget. Fred is not confident that the return on investment of the open floor plan is worth the added expense. So he makes a contingency plan to reduce the risk: If his house has load-bearing walls that prevent an open floor plan, he will either not buy that house, or he will change his plans.

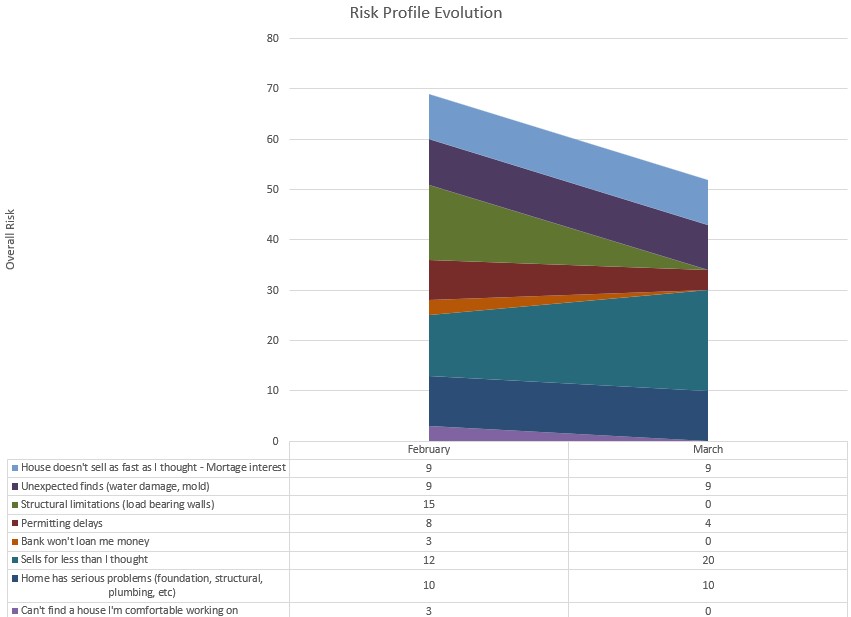

As Fred moves forward with his purchase and renovation, the risks on the project will evolve. Sometimes Fred’s mitigations are successful, and the risk drops or disappears. But other times unexpected things happen and risks grow.

He buys starts his property search in February and by March he has found a house he likes. Although the home inspection comes out without any major issues, there’s a key problem: There is a load-bearing wall in the way of his open floor plan. Fred makes an important decision: He gives up his open-floor plan. He does this to de-risk the project, but he gives up potential upside in sale price and the impact of financing/cost related issues becomes more serious. The risk profile has shifted like this:

Having eliminated a major source of risk from the construction phase of the project, the rest of the construction phase goes smoothly. But he can see it coming that his final sale price may be less than he expects.

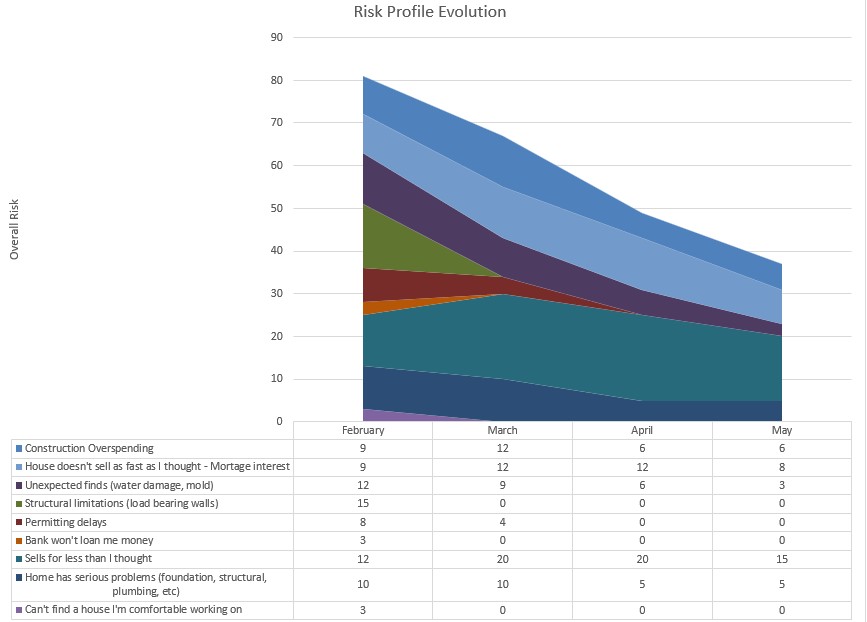

Fred starts working to mitigate these financial risks. He keeps closer eyes on construction costs, even adding their impact to the risk register so he can visualize all the risks together. He gets advice from his real estate agent on what cost effective things can be done with the appearance of the home to make a quick sale. On her advice, he invests in paint, landscaping, and staging the house to make it look its best for potential buyers. Fred feels these mitigation plans are successful, and he can see it in the Risk Profile evolution, but it’s hard to be sure until the house is actually sold. Like the old saying goes, “Don’t count your chickens before they hatch.”

Finally the renovations are finished and the house is sold quickly. Not as high a price as they had hoped, but they knew that would happen, and it was enough to cover the costs with some profit. It was not nearly as profitable as his friend had promised over coffee, but the result was positive.

Was Fred’s first flip a successful project? It certainly wasn’t a failure. But nor was it the sweeping success that Fred had been promised. It was something in the middle. He managed the risk, made the best of it, and finished with something positive in the end. And the lessons learned along the way make Fred confident enough that he could do another one at least as successfully as this one. In his eyes, that’s successful enough.

What’s your take? What should fictional Fred have done differently to make his project more successful than it was? What should he change going forward to make his next project better?

Let me know at brian.tompkins@ithacaglobal.com

Leave a comment